Credopedia

Mary Magdalene and other friends of Jesus

Among the female figures close to Jesus, one, Mary from Magdala stands out in a special way. That is why she has been called the “Apostle to the Apostles” since the Middle Ages.

What is this?

One of Jesus’ scandalous behaviours was his special closeness to women and his appreciation of their love. Jesus spoke with them at eye level. Women were noticed, protected and healed by Jesus. Women travelled with Jesus through the country. Women were probably the “financiers” of the Jesus movement. Women showed tender love to Jesus – and Jesus enjoyed it. Women were the first at the tomb and the first proclaimers of the resurrection. Among the female figures close to Jesus, one, Mary from Magdala stands out in a special way. That is why she has been called the “Apostle to the Apostles” since the Middle Ages. For a long time, it was assumed in the Church that Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus cast out seven demons, was identical with the long-haired sinner (prostitute) of Lk 7, 36-50 who anointed Jesus’ feet – but it seems not to be so. The confusion tempted novelists to bold imaginative exercises – when, for example, Dan Brown constructed a marriage of Jesus and Mary Magdalene or other authors wanted to conjure up a sexual relationship. One may well assume that Saint Mary Magdalene – whose feast day is July 22nd – was a strong, loving woman. The enchanting scene on Easter morning alone speaks for this, when she tearfully confuses the risen Jesus with the gardener until the sun of recognition flashes through. So, the sensual moments that many artists who painted “Mary Magdalene” included were more likely to come from another figure in the New Testament. This explains why she is venerated as the patron saint of repentant sinners, hairdressers and comb makers, gardeners, perfume and powder makers, wine gardeners, wine merchants, and the seduced. The fact that she is the patron saint of school children hopefully has nothing to do with erotic motives.

What does the Holy Bible say?

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus appears as an itinerant rabbi. In his company are not only the “Twelve”, but a whole series of women “who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities” (Lk 8,2). Named are “Joanna, the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza, Susanna”, but also “many others” (Lk 8,3). First is “Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out” (Lk 8,2). She is the first woman whom Jesus healed. It says the women “provided for them out of their resources” (Lk 8,3); in modern terms, they were sponsoring the Jesus movement. Mary of Magdala reappears under the cross (Mk 15,40), where two other women from the Galilean circle are mentioned: “Mary the mother of the younger James and of Joses, and Salome” (Mk 15,40). While most of the male disciples were conspicuous by their absence, Mary of Magdala and Mary the mother of Joses were present even in the bitter hour of Jesus’ burial (Mk 15,47). It is a testimony of faith that Mary Magdalene, Mary, the mother of James, and Salome opened their money chests to buy the precious and expensive oils and ointments to “go and anoint him” (Mk 16,1) on Easter morning- when they found the tomb empty. No wonder, then, that Mary Magdalene, so faithful and loving, was honoured to be the first to encounter the bodily risen Lord in person: “Jesus said to her, ‘Mary!’ Then she turned and said to him in Hebrew, ‘Rabbouni,’ which means Teacher” (Jn 20,16).

A short YOUCAT-Catechesis

Jesus and the Superwomen

Feminism seems to have just arrived in the Catholic Church, especially in Western countries, of course. Will we have women priests in ten years, women bishops in fifty years, and a female pope in a hundred years?

Feminism is not that old. The word only emerged in France in 1882 – one of the many consequences of the French Revolution and its basic demands for “liberty,” “equality,” and “fraternity.” There were many reasons for the violent protest against wrong relations of rule. One of the reasons was that the Christian roots of freedom, equality, and fraternity were buried. Only at the beginning did women benefit from the overthrow of conditions. In Delacroix’s famous painting, a bare-breasted Marianne was allowed to storm the Bastille, and a “goddess of reason” was enthroned on the altar of Notre Dame. But soon the revolution was a man’s business again. Freedom? Men followed their impulses more freely. Women were allowed to have abortions. Equality? From then on, women were also allowed to work in mines. And today they still have to fight for real equality. Fraternity? Women couldn’t do much with that anyway. We are still far from a truly fraternal relationship between the sexes.

The first great women’s liberation

The first great women’s liberation in the history of mankind took place in antiquity. Its operators were not the famous philosophers in Athens, but a simple man from Galilee who set new standards for dealing with women on an equal footing. The ancient Greeks were still operating within the framework of a practice in which women were second-class people and the property of men, even if they had a certain status as the wife of a free citizen. It was up to the father of the house whether he recognised a child he had fathered as legitimate and gave them an upbringing or whether he even abandoned them. In addition to the wife, who usually had her own area separate from the husband, other women could live or socialise in the house: Concubines, playmates at banquets (so-called hetaerae), prostitutes, slaves who were often recruited from surplus or abandoned children and raised and marketed by brothel mothers and pimps.

The model of one man + one woman + forever + children is exemplified in the book of Genesis where God creates an equal to Adam: Eve. The man rejoices: “This one, at last, is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” (Gen 2,23); and he establishes something crazy: “man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, and the two of them become one body” (Gen 2,24). This already sounds different, although it must be seen that patriarchal patterns continued to dominate in Israel as well. The patriarchs took concubines and great female figures were possible but remained the exception. The normal sphere of activity of women was the home. Only in the New Testament do women in large numbers enter the circle of vision of the prophetic figure of Jesus – and are perceived as human beings – with their worries, illnesses, obsessions, burdens, and sins. Jesus speaks at length, deeply and liberatingly with the Samaritan woman at the well (Jn 4). He protects the adulteress from the hateful mob (Jn 7). He has his feet tenderly anointed by a sinner unknown to him during a traditional men’s banquet (Lk 7). He is personally befriended by two women – Mary and Martha (Jn 10). And then women also join Jesus’ itinerant troop. That must have been simply shocking for middle-class Israel. You don’t do that as a woman.

And they paid Him back …

And the women pay Jesus back – not only in hard cash, although this should not be disregarded: someone has to pay for room and board at the end of the day. The women were simply better disciples in other ways: more fearless in danger, more faithful in their love, more instinctive in their faith. Their leading figure: Mary, the “God-bearer,” and right after her: Mary Magdalene. First, Mary Magdalene had to get the men on their feet. Then they too understood that Jesus was not a talker and that the Kingdom of God was not a flop. Her Lord, whom she had abandoned, had risen. Jesus had to guide the hand of the last obtuse man – an apostle named Thomas – into his wounds so that the penny would drop for him too.

Women also play a leading role in the early church: there is another Mary, the mother of Mark (Acts 12,12), who Peter goes to as soon as he escaped from prison. There is Phoebe (Rom 16,1), who is held in the highest esteem by Paul. And there is Prisca, the one with her husband (“my co-workers in Christ Jesus”) who “risked their necks for [Paul’s] life” (Rom 16, 3-4). The ancient Roman Canon, the first Eucharistic Prayer acknowledges the sacrifice of “Felicity, Perpetua, Agatha, Lucy, Agnes, Cecilia, Anastasia.” Behind every woman and martyr there is a great story: behind the slave Felicity, behind Perpetua, of whom we have a diary, behind proud Agatha, who was taken to a brothel by the Roman governor Quintianus, behind little Agnes, who died for Christ at twelve. One can understand Paul when he sees all social, ethnic, and gender differences levelled by the new beginning with Christ: “For through faith you are all children of God in Christ Jesus. For all of you who were baptised into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3, 26-28).

But women are not allowed to become priests!

To many women it seems a theological joke that women in the Catholic Church are allowed to do everything – look after children, clean churches, tailor vestments – but they are not allowed to become priests. St. Pope John Paul II put all his authority on the line and once again reaffirmed the traditional position of both the Orthodox and the Catholic Church: “Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter which pertains to the Church’s divine constitution itself (cf. Lk 22,32), I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church’s faithful” (Ordinatio Sacerdotalis 4). Many have marvelled at this sharp formulation of a Pope who can be considered, with good reason, a friend of women – there are countless testimonies of his esteem and sensitivity. And now he of all people – a final, woman-despising patriarch and battering ram of male domination? If there were no deeper theological reasons for assigning the priesthood to men, one would have to start a small revolution and stir up unrest in the Church until this stain is eradicated from doctrine. And indeed, that is what radical feminist theologians are doing, who have declared a kind of gender war on the Vatican. They think they can clarify the question on a sociological level – as a question of power, and as if it were a question of equal representation on corporate boards of directors or a kind of quota regulation at the altar. In reality, that would be a socialist approach. Justice does not mean “the same for everyone,” but “to each his own.” In the quotations in the YOUCAT there is a remarkable statement by St. Mother Teresa: “No one could have been a better priest than [Mary] was. She could say without hesitation: ‘This is my body’, because she really gave her own body to Jesus. And yet Mary remained the simple handmaid of the Lord, so that we can always turn to her as our mother. She is one of us and we are always united with her. After the death of her Son, she continued to live on earth to strengthen the apostles in their ministry, to be a mother to them until the young Church had taken shape.”

The Bride and the Bridegroom

As strange as the theological arguments may seem to people of the 21st century, they do exist, the theological reasons, and they are weighty, because they reach down into the depths of Revelation. From Adam and Eve onwards, the polarity of the sexes plays a role in Revelation. Christ is the “new Adam” (Rom 5, 12-21), Mary the “new Eve,” because “she speaks her ‘yes’ makes herself entirely available to the divine plan. She is the new Eve, the true ‘mother of all the living,’ namely, those who, because of their faith in Christ, receive eternal life.” (Pope Benedict XVI). The Church is the “Bride of Christ” (Eph 5, Rev 19), also in her gesture of receiving. Christ himself is “the Bridegroom” (Mk 2,20 and in many other places). The specific vocation of the priest is to symbolise and represent Christ as the Head of the Body (Eph 4,15) and precisely as the Bridegroom (Mk 2,19) – especially in the Eucharist. And only from this perspective is it understandable why there is the theological assignment of this ministry to men. Only in the horizon of gender is a woman the conceivable bridegroom for the bride, the Church.

YOUCAT 257 says: “In the male priest the Church should find Jesus Christ represented. Being a priest is a special ministry that also makes demands on the man in his masculine-fatherly gender role. However, it is not a form of male superiority over women. Women play a role in the Church, as we see in Mary, that is no less central than the masculine role, but it is a feminine role. Eve became the mother of all the living (Gen 3,20). As ‘mothers of all the living’, women have special gifts and abilities. Without their way of teaching, preaching, charity, spirituality, and pastoral care, the Church would be ‘paralysed on one side’.”

At the same time, it is true: clericalism exists in the Church and it is “a true perversion of the Church” (Pope Francis). Unfortunately, we still find clerics who have not understood that the priest is one who washes people’s feet after the example of Jesus. A “priest” only works as a humble service. There is no two-tier system in the Church. Ordination is not an entry into the premium class and certainly not a joystick for arbitrary rule. That is why YOUCAT 257 also says: “Wherever men in the Church use the priestly ministry as an instrument of power or do not allow women to have a role with the charisms proper to them, they offend the love and Holy Spirit of Jesus.” Women still have their future ahead of them in the Church – not in the role of “priest”, but everywhere else.

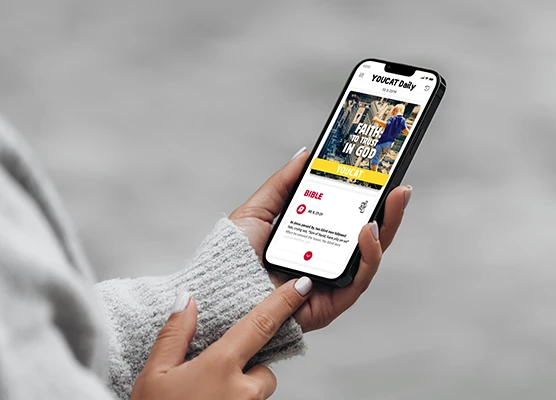

YOUCAT Digital

Discover our digital products, which will help you to grow in faith and become missionaries yourself.