News

Corpus Christi – all for show?

Definition

Since the year 1264, the Catholic Church has celebrated the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of Christ with a solemn procession. This celebration takes place on the second Thursday after Pentecost. In many countries, however, “Corpus Christi” takes place on the following Sunday. This celebration recognizes the abiding presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

What does the Bible say?

At every Holy Mass the Church fulfills the mandate of Christ, who on the evening before his death instituted the Holy Eucharist and commissioned his disciples: ” Do this in remembrance of me” (1 Cor 11:24). In doing so, the Church takes literally the words that Christ spoke over bread and wine: “This is my body… this is my blood” (Mk 14:22-24). This faith in the literal presence of Christ (real presence) in the transformed gifts of bread and wine has become ever stronger in the history of the Church, so that the Council of Trent (1545-1563) solemnly defined that in the Most Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist “the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and therefore the whole Christ, are truly, truly and substantially contained. On Corpus Christi, the whole Church publicly confesses Christ’s provocative words: ‘I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world’ (Jn 6:51). In the transformed bread, the world sees the beginning of a transformation that has already begun and will one day encompass all that has been created, for we are expecting a “new heaven and a new earth” (Rev 21:1).

A short YOUCAT-Catechesis

Corpus Christi – all for show?

Martin Luther, as we know, was no friend of the Corpus Christi procession. He said in one of his toasts that he was “of no feast more hostile than this. Because it puts most shame on the holy sacrament, that one puts it on for show, and vainly makes idolatry of it.” That’s a strong word.

Was this “idolatry”, that is, idol worship, – this effort that was made in my home region to make the feast of Corpus Christi the early summer highlight of the whole village? The festive event drew believers and non-believers alike onto the streets – some as spectators, others as participants. Young birch trees were cut, their greenery lined the path of the procession, metre-long flags were hung out of the windows. Mountains of grass were mowed to cover the grey of the pavement. Court entrances became altars. Everywhere, flowers shone in the window niches and candles flickered in the wind, their wax dripping onto preciously embroidered cloths. The people stood in a trellis.

And then the mystical drum approached, wrapped in a picturesque cloud of incense and brass music: the great procession, the carrying cross in front, First Communion children scattering rose petals, delegations of flags of the associations, large fire brigade deployment. Under the “roof” (a portable fabric roof): the monstrance, the holy golden showpiece, which carried the mysterious core for the enormous effort in its middle: a small piece of tasteless bread, multipliable by billions, of course endlessly loaded with meaning through a word of Christ: “This is my body for you…”. (1 Cor 11:24)

Is Luther not right? Strictly speaking, the primal scene with Jesus was about a festive supper. In YOUCAT 208 it says: “When we eat the broken Bread, we unite ourselves with the love of Jesus, who gave his body for us on the wood of the Cross; when we drink from the chalice, we unite ourselves with him who even poured out his blood out of love for us.”. And shouldn’t we just have another festive meal if we want to follow Jesus’ invitation: “Do this in memory of me” (1 Cor 11:24)? Instead of running around outside and making a show of it, with some showing their faith and (some just) their clothes, while others mockingly twist their lips?

Is there nothing to see? Just to eat?

From Pierre Rousselot, a young Jesuit who died in the First World War, the word comes from the “eyes of faith”; he meant the supernatural power of knowledge of love. It may be that the one who sees nothing in this piece of bread around which everything revolves, but for the other, who recognizes love in love, a world opens up.

In 2002, a man died who is revered as a hero in his homeland Romania. Alexandru Cardinal Tódea had spent 31 years of his life in communist prisons, of which 15 years in solitary confinement. Once, after years, the priest was transferred to another prison. Tied up in the railway carriage, he saw his guards from the secret service “Securitate” unpack their bread and open a bottle of wine. Tódea was hungry. But another longing burned in his eyes: “My God – I could not celebrate Holy Mass for so many years. And there is bread! And there’s wine!” Finally he asked the guards: “Give me a crumb of bread and a sip of wine!” One of the guards took pity on him. He couldn’t see the vibrations going on inside the priest. The invisible Eucharist in the rumbling railway carriage was the most intense of his life. Here he had received the strength to endure all the torture, humiliation and loneliness that would come upon him.

Throughout the history of the Church, there have always been people who were ardent supporters of an invisible spiritual reality, such as the 49 martyrs of Abitene, who were executed in 304 by Emperor Diocletian for two offences: First, for refusing to publish the “holy books”, and second for holding fast to the celebration of the Holy Eucharist: “Do you not know”, the priest Saturninus is said to have defended himself, “that the Christian exists for the Eucharist and the Eucharist for the Christian? Why is that so important? In YOUCAT 180 it says: “In the Eucharist, Christ gives himself to us, so that we might give ourselves to him.” Surrender in exchange for surrender – that is the essence of Christianity.

To show something of Jesus…

To show something special about Jesus was the idea of a parentless 16-year-old in the 13th century. Liege must have been something of a spiritual hotspot back then. There was a movement there that was fascinated by a single thought: Can it be that the Lord in the forms of bread and wine is so real even now and today that one can only kneel before it? Pope Benedict once called the Liege of those years a “Eucharistic cenacle”. In the middle of it: a girl called Juliana. In 1209 Juliana had an idea – not really an “idea”, but an inspiration in prayer. One would have to make a glorious feast out of the Eucharistic presence of Christ! Holy Thursday alone was not enough, where the mystery of Christ’s love was hidden as if under the shadow of the cross.

This was not a foolish idea of an overexcited youth. Fifty-five years later, the feast was being held all over the world. In 1264 Pope Urban IV introduced Sollemnitas Sanctissimi Corporis et Sanguinis Christi – the “Feast of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ. A lot had happened in the 55 years in between. Among other things, the brightest minds of their time – above all the Dominican Thomas Aquinas and the five years older Franciscan Bonaventure – were studying the mystery of the Eucharist. In fact, we still sing the brilliant songs Thomas created at that time – the Adoro te devote (I devoutly adore you), the Lauda Sion (Your Saviour, Your King), the Pange lingua (Sing, my tongue, the Saviour’s glory), the Tantum ergo (Down in adoration falling). The texts were so inspired and powerful that – so it is said – Bonaventura simply threw his own attempts into the trash.

Beauty comes back

The feast of Corpus Christi opens the view on two very beautiful realities: First, in the midst of the absence of love and hope, in the midst of the great silence about God, people become visible to whom something is extremely precious. It seems that there is something that is worth any price, but that money cannot buy. Perhaps it also becomes visible that “man is never greater than when he freely and devoutly kneels down before God.” (YOUCAT 485) Second, people carry Jesus onto the street with gratitude and rejoicing. For he does not belong into the church. Jesus has come to redeem the world. For this he has spent himself on the cross. We all learn anew that Jesus took bread and wine “to offer in them to God all of creation, transformed. For we, too, are transformed and redeemed by Jesus, and so from the depths of our hearts we can be grateful and tell God this in a variety of ways.” (YOUCAT 488)

Something paradisiacal – a fragrance, a shine – comes back to our cities, villages, biographies.

How could an “Updated Corpus Christi” look like?

“Definitely not purist,” says Benjamin Leven. “It fits perfectly with the times when old pomp and modern creativity are combined. What would happen if next year in a bishop’s city all creative energy were put into the preparation of this feast? The evening before, a mystery play would be performed on the cathedral square, specially written by a contemporary writer. The flower carpets at the stations would have been designed by street art artists. The procession would include a samba chapel. After the procession, the bishop would invite a thousand poor and homeless people to a meal on the cathedral square and serve them personally. And in the evening the feast would end with fireworks.”

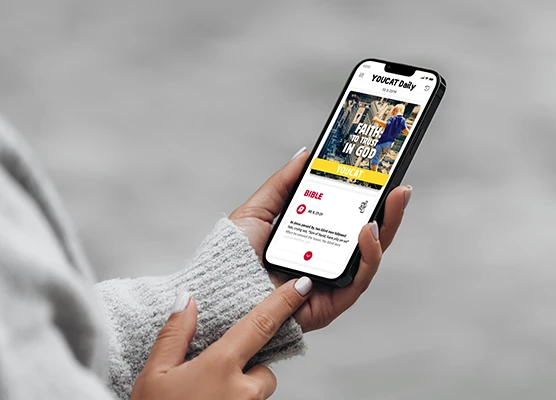

YOUCAT Digital

Discover our digital products, which will help you to grow in faith and become missionaries yourself.